The appearance of the Virginia Minstrels represented a signal shift in early blackface minstrelsy. The members of the band—Dan Emmett, Billie Whitlock, Dick Pelham, and Frank Brower—were all well-known blackface performers before joining forces in New York. Brower had been performing in Philadelphia since arriving from Baltimore as a 13 year-old dancer in 1836 and had travelled with Emmitt, a Mount Vernon, Ohio native, in the Cincinnati Circus. Billy Whitlock was established as a co-author of the popular “Lucy Long” along with T.G. Booth while Pelham was known for composing and performing “Massa is a Stingy Man” with his brother Gilbert. The Virginia Minstrels mostly sang established songs like “Lucy Long” and “Jenny Get Your Hoe Cake Done,” but also added new numbers like Dan Emmett’s “Ol’ Dan Tucker.” What made the Virginia Minstrels distinct from T. D. Rice’s “Jim Crow” and the other solo acts and duets was the way they combined music and comic antics. When in their classic semi-circle, Whitlock and Emmitt played the banjo and fiddle in the middle while Brower and Pelham performed as comedians and play the bones castanets and tambourine. Brower and Pelham were known primarily as dancers but it was their jokes, commentary, stunts, and pratfalls that infused the Virginia Minstrels with the manic energy for which they became famous. After a sensational first run at the Chatham theater in New York, the group sailed east for tours of Ireland and England where they were joined by J.W. Sweeney for several performances while also splitting off with duos of Brower and Emmett and Sweeney and Emmett performing on their own. The Virginia Minstrels broke up in 1844 but their success inspired other blackface performers to form bands like the Virginia Serenaders, Ethiopian Serenaders, and New Orleans Serenaders.

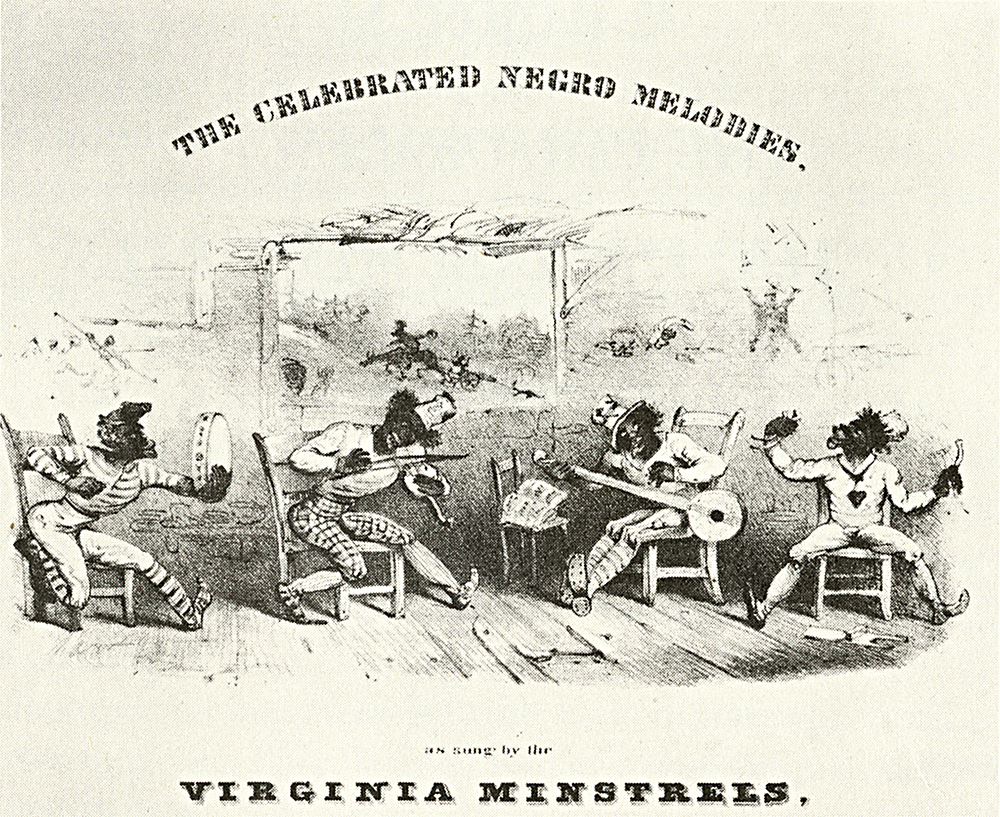

The above picture of the Virginia Minstrels had a pervasive phallicism. The phallicism wasn’t limited to the little penis showing between the splayed legs of Frank Brower on the group’s left, Brower’s feet are also portrayed as erect penises. So are Emmett’s feet and Dick Pelham has a penis foot showing as he prepares to punch his tambourine. The Edward Clay lithographs portrayed the feet of black men and women as phallic with their exaggerated size and extra-long heels also giving black feet an animalistic effect. But it would be more accurate to say that the the cover illustrator substituted erect penises for feet with the Virginia Minstrels. That is except for one of Emmett’s feet where the front of the penis foot is deflated as if it is going flaccid. There is also a flaccid penis effect with the tongues of Emmett and Whitlock as they play their fiddle and banjo which imparts somewhat of an opposition between erect and flaccid penises to the whole picture with the erect penises including one of the castanets held by Brower and Emmett’s banjo. Eric Lott noted in Love and Theft that banjos were often pictured in phallic ways and argues that blackface had an obsession with “the black penis.” Such an obsession could be there but it would be part of a general play of penises in the picture. The Virginia Minstrels were white men performing as black men and the pictures could also be seen as representing white penises through the vehicle of blackface performance. By picturing penises as feet, the picture also represents penises as being detached from their ascribed place on male bodies. There’s a sense of endless play with penises in the picture of the Virginia Minstrels but also a kind of vulnerability that can be seen in the picturing of Brower’s blackface penis with his legs being splayed.

Penises being detachable raises another possibility in relation to early blackface minstrelsy, the historical literature on blackface minstrelsy portrays white blackface performers as stealing black folk figures, dance styles, clothes, skin, hair, musical instruments, and dialect for the purpose of entertaining white audiences and enabling white men to sustain a functional identity during the hard times of early industrialization. It might be that the Virginia Minstrels were aiming to take black penis as well and that the fascination with “the black penis” was something that accompanied a determined effort by white performers and audiences to steal black penises and use them for white purposes.

A general thesis from this consideration would be that the Virginia Minstrels viewed white identity as demanding that whites possess everything blacks have, everything blacks are, and everything whites could ascribe to them. In other words, they demanded an insanely high level of cultural ownership.

1 Comment